Our History

A Trade Begins (1800s):

Electricity was introduced to Melbourne in 1867 to celebrate the visit from the Duke of Edinburgh. Parliament House, the Post Office and the Telegraph office were lit up with arc lamps supplied from a series of chemical batteries.

1877 the Apollo Stearine Candle Company were the first to light their factory for night work. By appointment, the manager could take you on a tour to see this strange new technology; an arc lamp supplied by a dynamo.

13 August, 1879 the first night footy game happened with arc more lamps lighting the MCG. Carlton played Melbourne in the mud. The lights proved un-successful as the players were either blinded or lost in the shadows. 7000 people watched Carlton win 3 goals to nil.

1882 the Athenaeum Hall was lit by arc lamps and they were so impressive the Opera House Company lit up their auditorium with 120 lamps.

Suddenly electricity was being taken seriously. Supply companies began to pop up across Melbourne like mushrooms; poles carrying electric wires and transformers began to line the streets. Incandescent lamps had been developed and young men were going off to college to study electricity and then looking for careers in it.

To the Melbourne Town Clerk,

Having completed my course in Electrical Engineering at he Ballarat School of Mines and being desirous of obtaining employment in the City of Melbourne Electrical Lighting Station I beg to apply for the position of electrician…

Isidore G. Wittkowski.

Then, just as the new technology began to take off, the onset of a 1890s depression spread over the industry, weakening many of the supply companies and causing some to fold.

But the Melbourne City Council consolidated its place in electrical technology by building a new power house in Spencer Street and by March 1894 twenty General Electric dynamos supplied 3000 volts to a network of lighting with some sixty miles of street cables cris-crossing the city. In Victoria 175 electrical men were working in this new industry.

But by the turn of the century all the supply companies had been cut back by amalgamation and the number of electrical men recorded in Victoria had reduced to 147. The industrial climate was demanding they organize themselves.

1900s Electrical Men:

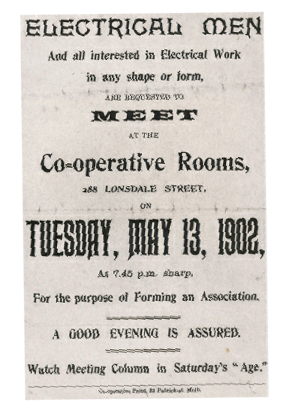

They put posters up around town and on a warm, Tuesday evening in 1902 ninety-one electrical men gathered in the co-operative rooms at 28 Lonsdale Street to form themselves into a union.

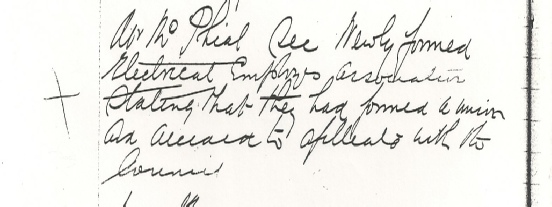

They called themselves The Electrical Employees Association and elected their officers. Ed Giles was elected President, Bill Stewart, Vice-President, Isidore Wittkowski Treasurer, and Andy McPhail became the first Union Secretary. Fifteen days later Andy McPhail attended the THC meeting to have it recorded in the minutes of the meeting that Electrical Employees Association had been formed and was now operating.

They called themselves The Electrical Employees Association and elected their officers. Ed Giles was elected President, Bill Stewart, Vice-President, Isidore Wittkowski Treasurer, and Andy McPhail became the first Union Secretary. Fifteen days later Andy McPhail attended the THC meeting to have it recorded in the minutes of the meeting that Electrical Employees Association had been formed and was now operating.

This was a decade of ETU infancy, born as the Electrical Association of Australia. It changed to the Wiremen’s union and by 1908, had become the ETU of Victoria. It was a period of building on a beginning and establishing good relations with the electrical trade unions in the other states while raising the idea of a national union. In those first seven years there were three union secretaries, Andy McPhail, Joe Horton and Vern Gunst.

But by 1910 the foundations were solid and strong and led by Secretary J. Vern Gunst. It was at this time ETU member, Arthur McKoy was killed by electrocution while up a pole in Carlton. The ETU shouted loudly about profits being put before safety and focused the need for the licensing of the trade being a necessary to protect the quality of work with a killer technology.

“Before a plumber is allowed to attack the sanitary works of a building he must be licensed, showing he is a competent man; yet all an electrical wireman needs is a pair of pliers and he can let dangerous electric current into a building which may kill or set a building on fire.”

As the decade came to a close, these issues along with wages and conditions would be the platforms on which the union would stand.

1910s:

This was the decade of coming of age. It was a time when electrical wages boards were established for supply and installation and the union successfully negotiated electrical awards to function within them.

Electrical men were crossing state borders and there was a need for wages and conditions to travel with them. The ETU led the way, applied to the courts and became a national union, ‘The Federated Electrical Trades Union of Australia’ in 1912. Vern Gunst became National Secretary and along with Bill Stewart who became President they traveled interstate organizing and bringing together the electrical unions of other states.

During this time the union employed its first organiser, Jim Hudson. Jim would be the only organiser until he died in 1943; his descendants are still proud ETU members.

In 1917, Victoria got a new Secretary in Albert (Snowy) Henderson who would preside over his union as its leader for the next 41 years.

Licensing:

At the end of 1918 the Electricity Commissioners’ Act was passed by the Victorian Legislature placing the administration of installation and supply of electricity under the control of three commissioners. But important for electrical trades was that after a five year campaign by the ETU’s President Chas Willers, Snowy Henderson, it became law that those who carried out electrical work for gain or reward would have to be licensed to do so.

1920s:

By 1920 three grades of license had been created: ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘C’ grades. But the union was not happy about the administration of wiremen’s licenses. Secretary Henderson expressed concerns: ‘…The Commission should appoint an employees’ representative on the Board of Examiners, seeing that it was mainly through the efforts of us, ‘The Union’ that the licensing system became law…’

The ETU was growing with the trades and, in 1923 it set up a sub-branch in Morwell, increased its delegates at the ALP conference to three and signed the anti-communist pledge.

The union also campaigned for electrical trades to be proclaimed apprenticeship trades by the Victorian Apprenticeship act. That happened in 1927 and an apprenticeship committee was formed for the electrical group. It consisted of three employer members and three union members and it meant that proper trade training rather than ad-hock learning could be developed and put into place for electrical trades.

1930s:

While the 1930s was dominated by the Great Depression electricians struggled less than most as the technology continued to grow. But some did struggle, particularly non-trade electrical workers and Snowy Henderson’s family still tell of how he, the union secretary, would come home with only half his wage; the other half being handed out to out of work unionists sitting on the grass outside of Trades Hall.

The 1930s was also a decade of political intrigue. On 15 October 1930 a special general meeting of ETU members was called to consider their relationship with the ALP. Members were not happy that their approaches to the Scullen Government were falling on deaf ears. Members wanted to make the politicians sit up and take notice and a motion was put up that the union disaffiliates from the Labor Party.

After robust discussion, Union Secretary, Snowy Henderson, put up an amendment that …The Electrical Trades Union withdraws its affiliation with the Australian Labor Party for six months as an indication of its dissatisfaction with the Labor Government failure… to deal with unemployment and the attacks on wages and working conditions. The amendment was carried and the union temporarily severed its ties.

The ETU also dominated inner city councils such as Brunswick and Collingwood. In the mid 1930s ETU members as city councillors used their numbers to win the 40hr week for workers in their municipalities long before it became a national victory.

And still licensing was a quest. In 1934, ETU member and Labor MLA, J.J. Holland used his influence to get a bill passed making it a requirement for Electrical Contractors to be licensed.

Because the membership was becoming too big for all the members to gather to make decisions, as in a direct democracy, a governing body of members was elected to come together and oversee the running and policy making of the union as in representative democracy. In 193? a State Council was created.

1940s:

The 1940s began with WW2 and the ETU working closely with the SEC and the Government to prevent rat-bag employers from using the dilution of labour regulations to win contracts by undercutting the genuine employers with cheap unskilled labour. ETU member Jock Innes was seconded to the Government Directorate of Manpower to oversee the correct use of labour skills in the electrical industries.

In 1946 the ETU’s long serving secretary, was appointed as a commissioner of the SEC. Initially his appointment was welcomed by members seeing it as a workers voice in power generation industry. But it wasn’t long before members began to see his appointment as having one foot in each camp; that of the worker and of the employer.

As the fight for a 40hr week became national, the general mood of the Victorian membership was changing. When the members wanted to walk off the job and fight for the 40hr week, Snowy said not while the matter is in the courts. This frustrated particularly left wing members who openly said they did not like their union being a ‘Tame Cat’ union while other unions were out their fighting industrially.

Politically the ETU, aligned closely with the ALP formed a right wing Industrial Group which worked actively against Communist control of the union within its officers. But the membership was splitting and the Groupers were destined to become out of tune with the rest of the membership.

1950s:

This decade was a period of growth. Membership reached 11,000, there were about 27,000 new consumers being connected per year, the SEC was putting up a new pole every seven minutes of each working day and connecting a transformer in every one and three-quarter hours. Industrially, Secretary Henderson told the membership that, because we had had no unauthorised stoppages to prejudice proceedings, the ETU was the leader in the fight for margins. The margins were the difference between the basic wage and a tradesman’s wage.

But his words didn’t change the mood of the members. They were feeling humiliated when they were left behind on the job while others were walking off to fight. That mood caused a leadership change the destruction of the Industrial Group and a affirmation of an alliance with Dr Evatt’s Labor philosophies. Snowy Henderson stepped down as union secretary, a new era began, and the union began a fight for the creation of a Contracting Industry Award.

1960s:

In this decade the ETU membership was determined to fight industrially rather than in the courts. Jock Innes, the new union secretary was in tune with the mood and said; Members who take a keen interest in their Union and who are prepared to act and not talk (thereby getting stronger support of their Union officials) will win demands to which they are entitled.

And after two years and more than 1000 disputes across three states its first win was the Contracting Industry Award.

But there were penal clauses in Government legislation that imposed fines and the threat of jail on unions that took industrial action. The union and shop stewards began to look for inventive ways of fighting as they, at last were feeling proud to be taking the fight up to the employer rather than in the graveyard of industrial disputes, as fighting in the courts became known.

Special Class Fight: In the latter half of the decade the important achievement for electrical workers was that of an Electrical Special Class classification. Ironically this was won in the courts it was recognized by the Arbitration Commission in December 1967 that electrical trade technology was going beyond the basic craft levels of expertise and it should be recognized. The Electrical Special Class grade paved the way for future grading and, therefore, career paths, for future electrical workers, beyond the A grade electrician or electrical fitter. In June 1969 the new classification of Electrician Special Class was introduced into the Metal Trades Award with a pay rate of $64.90.

But the ETU had paid a high price for its militant transformation. By the end of this decade the penal clauses imposed had been used to fine ETU ₤16,350, which was six times as much as all the employers put together and in only half the time.

This was the era of the Innes dynasty with Jock Innes controlling the union in the first half of the decade and his son Ted becoming secretary for the latter part. Politically, the ETU had a close first name relationship with Federal Labor leader Arthur Caldwell and Victorian Labor with Clyde Holding and Bob Hawke. In his memoirs, Hawke described Jock Innes as a surrogate father while Ted became Victorian treasurer of the Labor Party and formed the Centre Unity faction with Hawke and Holding and then left the union to become a member of the Whitlam Government of 1972.

1970s:

This decade began with a new union leader and a program of rebuilding after the financial burdens of the penal clauses. Charlie Faure took control, introduced tough spending restrictions, organizer accountabilities and carried the union further to the political left.

The building industry was growing; the membership continued to fight for contracting industry award improvements and employers wanted peace. The ETU capitalized and gained much for its members in construction during these times.

But in the power industry it was different. Bitter disputes between the State Electricity Commission and power industry workers began. Arbitration failed. Black-out tactics were used by the State Electricity Commission and communities suffered until ACTU leader Bob Hawke brokered a deal alongside the Metal Workers secretary, John Halfpenny. It suited some unions but not the ETU. Ian Berwick the union organizer for the Latrobe Valley where the power stations were situated, summed up the feeling of betrayal when he said on the public record, ‘Let’s say – there’s a couple of people I’ll never forgive!’Even so, the union finished the decade looking good. A State Councilor said; ‘This was a period when the union went from boiled lollies to rolled gold chocolates.’

1980s:

This was the decade of restructuring and amalgamations, accords, asbestos and creosote poles. It was a time when the Hawke Labor Government, in bed with the Australian Council of Trade Unions, implemented industrial changes to support its economic rationalist policies. The theory was that it would make us more internationally competitive. As part of it, ACTU secretary Bill Kelty came up with a blue print to restructure the union movement by amalgamating many smaller unions into bigger ‘Super Unions’.

The Accord:

The Prices and Incomes Accord was an agreement between the Australian Council of Trade Unions and the Labor Government made in 1983. Unions agreed to restrict wage demands; in return, the government pledged to minimise inflation and give an automatic periodical wage increase.. It meant the Labor Government and the ACTU wanted to take control of industrial relations There were ???? accord during the life of the Hawke government and a drop in the real value of wages by about 16%..

Fight against Amalgamations:

The Bill Kelty blueprint to amalgamate small unions into much bigger unions was a major concern for the ETU. As a craft union it could have meant the loss of focus on the electrical trades by whichever super union it was swallowed up into. Had the ETU got it wrong, it could have spelt the death knell for the union as it is known today.

The ETU, nationally, decided to amalgamate with another small right wing union, as a way of maintaining its craft base while increasing its size to something big enough keep it out of the super-union framework. It chose the Australian Society of Engineers a small union with similar aims. But while the Secretary and his supporters were in favour of the amalgamation, the Assistant Secretary and his supporters were not. A members’ campaign crossed boarders into other states as they lobbied for a vote against this amalgamation. They succeeded and the amalgamation with the ASE failed. The campaign caused a leadership spill; the elected secretary and his supporters were ousted and the Assistant Secretary and his supporters took control of the union.

Award Restructuring and Multi-skilling:

The ETU was supportive of some principles of restructuring but vehemently opposed to others. It supported simplified awards with career paths but opposed multi-skilling, arguing it would cost jobs. It opposed removing of penalty rates, staggered start-finish times and time off in lieu of overtime payments.

Licensing of Electrical Trades:

Licensing of electrical trades was also tangled up in the restructuring of industry. The AMWU became predatory as it looked to take some of the work done by electrical workers to replace disappearing work of their own trades. That union lobbied hard to demolish licensing of the electrical trades and, therefore, make it easier to achieve their goals. Restricted licensing was introduced whereby those other than electricians could be licensed to do specific work under restricted licenses.

Beyond that, the union and its members fought hard against the use of asbestos in the workplace and the cancerous creosote soaked electricity poles being erected. These two issues have become foundations on which the union fights today.

1990s:

The 1990s began for the ETU amalgamating with the Posties, Plumbers and the Telecommunications unions to form the Communications, Plumbing Electrical Union, ‘CPEU’, but within that amalgamation the ETU members demanded an autonomy and independent identity.

Enterprise agreements principles were introduced by the Keating Labor Government in 1993, and were the beginning of a new way of bargaining for wages and conditions. The argument, that workers and employers would be better served by wages and conditions being negotiated with each individual employer rather than in a national award, set varying standards across the nation. Watered down awards would remain as a safety net with only the basic fundamental rights protected by them.

The reality was that the stronger the workforce the better it would be able to argue for better wages and conditions. The smaller or weaker workplaces would have little to argue with and would be at the mercy of the employer’s generosity. The union had to change its way of thinking and the way in which it negotiated. That would be pattern bargaining.

At was also a decade when the union revitalized or recharged itself with a new leadership and a new vision for the future. The recharged ETU used the strategy of pattern bargaining where, particularly in contracting, all enterprise agreements would be the same and agreements would come into effect at the same time. The advantage for employers was that of a level playing field and protection from the shonky contractors undercutting the rest. An advantage for the union was that administratively it didn’t have to negotiate thousands of individual agreements separately.

It was also a time when the campaign for shorter hours of work was stepped up and the 36hr week was won in many areas of the contracting industry.

2000-2020: The Challenge of Change

As the Union moved into the new millennium it needed smart thinking to build a strong and wealthy organization and by now it was creating innovative enterprise agreements that protected workers’ rights, wages and conditions from the anti-union WorkChoices legislation. But Conservative Governments changed their legislation attacking the innovation and outlawing those new ways of protecting workers rights and hard fought for wages and conditions. The union has had to change and adopt new indutrial relations thinking.

In 2002 and 2014 the ETU was brought before ‘union corruption’ Royal Commissions and because of its innovative style of unionism it was scrutinized like no other. No corruption was ever found nor any charges laid as the ETU came out of the courtroom clean and proud to be union.

Also in 2002 this union won shorter working hours in the contracting industry when, in most workplaces, working hours were increasing. The 36hr week won for those workers proved shorter hours would not break the back of businesses and industries. As the ACTU President, Sharon Burrows said;

The ETU’s commitment to work-life balance and indeed to work and family has been remarkable…

But the industrial landscape had become an environment of constantly changing legislation. Enterprise agreement clauses were being outlawed by Government, and this union began to negotiate legal deeds to catch clause after clause thrown out of agreements. The deeds were subsequently outlawed by anti-union legislation. The changing legal complexities of enterprise agreements, and individual contracts meant lawyers had to be involved.

Workers became shackled by WorkChoices, the Building Industry Codes of Practice, the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) and the Registered Organisations Commission. Regulations came with the threat of fines and the fear of jail terms on individual workers and the unions that represent them. Yet, in spite of it all, electrical trades enterprise agreements have been the envy of most.

But while the union needed the smart thinking to meet the challenge of change it also needed the toughness of traditional unity in unionism. So often employers have locked their workers out of the workplace, saying they would not be allowed back without savage reductions to their wages and conditions. Time and again workers have had to tough it out on the grass, as is the union term, with support from this great union and the rest of the union movement, until those ratbag employers agreed to fair and reasonable outcomes.

In the power industry, the ETU concerned itself with the electricity supply and distribution across the state. After privatisation of the power industry, the condition of the network was seen to deteriorate. This union campaigned loudly on the state of crisis of the power industry before, during and after the Black Saturday bushfires of 2009. After the bushfire Royal Commission, the ETU played an integral part in the Government’s response to lifting the standards of maintenance. It championed the tightening of electrical licensing requirements including the licensing of lines-people and the lifting the standards of maintenance required.

Licensing of the electrical trades is about safely working with and installing a technology that kills. Throughout its history this union has constantly defended the licensing system in order to keep safety standards high. To that end it has worked with present day Government to strengthen regulatory requirements and the introduction of ‘A’ grade licence refresher courses, again to maintain the standards required by law.

During this period of constant attacks on unions the relationship between the National body and the network of state branches across Australia began to fracture under the strain. Under the new leadership of Troy Gray, the Victorian branch led the way to healing those fractures.

At the 2014 Victorian shop stewards conference, for the first time ever in the history of this great union, the leadership of the National and all branches of the union came together. It showed a united front and put on show the new leadership being forged.

As part of that healing process, Troy Gray led a rule change that paved the way for all branches to have autonomy in the way they invest for members benefits. Wise investments have enabled the Vic branch to grow fiscally stronger and so increase the benefits to members.

To that end, the ETU as worked tirelessly to shape the content of industry training and ensure members have the skills they will need into the future. It is why, in 2016, this proud craft union set up the second floor of the union building as an award-winning TAFE trade training campus which it named Futuretech.

Beyond trade training, the ETU has always promoted and supported the welfare of its members and their families. And to that end, in 2019, it set up the top floor of this union building as an employment and welfare centre’ which it named the Centre for U. The Centre provides assistance for members, including reskilling courses, financial advice, health checks, legal advice and help with personal issues.

And through it all, the ETU has continually maintained a policy of Community involvement and support. Members and community groups can and do apply for union grants to support their community activities such as junior sports, fundraisers, and support for migrant programs.

So, as the ETU stands today the fight for working people goes on alongside the protection of the trade and support for the communities in which its union members live and work.

For more union history, including the story of Sparkies at War, make sure you visit the web site of the ETU's historian, Ken Purdham: www.kenpurdham.com